This is where you could have died when you were four. Your tiny body smashed against the tree trunk, your back bent into an impossible zigzag of broken bones, your ribs forced in all directions, your kneecaps catapulted to the back of your wriggling legs, your head cracked wide open like a pomegranate, its bloody seeds raining through the fissures of your skull onto the ground.

The roots of this tree I stand upon today would have heard you scream as you kicked your legs every time they beat the bark with your body, an internal Hiroshima of gastric juices running down your chin, leaves falling on your forehead as you shook the tree with the fury of your fear.

I look at the tree and the thought of you dying right here is unbearable. The unfathomable extent of human cruelty, how men and women forsook their humanity, turned on each other, and high on ganja and empty promises battered children against this very chankiri tree. To ensure the establishment of the UCKMR — Ultra Communist Khmer Rouge Regime — soldiers murdered their prisoners with poison, with bamboo sticks sharpened into spears, with throat-slitting blades made of thorny leaves. They threw their victims off cliffs and dumped their mangled bodies into deep caves. To save ammunition. An extreme measure under an extremely austere war. But children’s skulls are acutely tender, so light, so easily broken when bashed against the trunks of chankiri trees, that after a few blows their eyes popped out of their sockets and their necks hung lifelessly over their chins. When they stopped crying, after the last gulp of tears, snot, and blood went up their nostrils, when they no longer called for their mothers, their little bodies were flung into pits, shallow mass graves filled with twisted bodies and mouths contorted into silent screams. To stop the little bourgeoisies from growing up and taking revenge for their parents’ deaths. To stop another generation of intellectuals from ruining the Khmer Rouge dream of a back-to-the-roots Cambodia; a Shangri-La nation of slaves with no room for education or tolerance for the arts; where no one reads, no one writes, and no one sings; a warped notion of a deaf and mute paradise of illiterate citizens, where the only music allowed was the cacophony of ancient hoes breaking up soil.

I try to imagine Cambodia on 17 April 1975, when a man named Pol Pot and his army marched into Phnom Penh. They called themselves the Khmer Rouge — the Red Khmer. Khmer because it is the main ethnic group of Cambodia. And red because they wore the karma, a red-and-white checkered scarf, around their necks. Within 48 hours, the Khmer Rouge had complete control of the capital. Everyone was forced to leave their homes and relocated to work camps called collective farms. In three days every city was empty. Pol Pot believed that city people had been corrupted by capitalism and there was no room for them in his utopian, pure communal society. Therefore, they had to be exterminated. The year 1975 was Year Zero, a historical moment of Cambodia’s new beginning, all under the absolute and unequivocal control of a single man: Pol Pot. In just three years, eight months, and 20 days, his Khmer Rouge had murdered about three million people.

*****

I met you at the gym where everybody assumed you were Hispanic. Other Latinas thought you were a snob for not speaking Spanish. There you were, the way I remember you, gyrating your hips to a cumbia, pumping your chest to a reggaeton, whipping your hair left and right as you did the mambo. There was a fiery cadence to your dance moves, the kind of passion one feels when dancing to one’s own music. Your brown skin, that flirtatious smile, and the stereotypical sex appeal attributed to South American women made me also think you were Hispanic. Only you were Asian. Born in Cambodia, you had lived as a refugee in Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam before being relocated to the USA. You were a political refugee, a dance instructor, married to an American man, mother of two children, and my dear, dear friend.

“What’s the story of your scar?” I asked you one muggy Florida evening as we left the gym. You let out a dramatic sigh and asked me if I would like a drink. We had been working out and I found the idea of a freshly squeezed lemonade with crushed mint leaves very appealing. You had something else in mind. We walked to a nearby sports bar and you ordered two shots of tequila and a G&T with lots of gin and little tonic. I sipped my iced water and wondered how your petite body would handle such a cocktail after our gruelling workout.

“My scar,” you said, rubbing the inch-long mark on your forehead. “Do you want the long or the short version?” I shrugged my shoulders in a whichever-version-you want-to-give-me way.

“Short story goes like this: it’s the ‘70s in Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge are all over the country, arresting and killing non-communists. My family is not a sympathiser of their cause, so my parents leave in the middle of the night. My two brothers, two older sisters, and a baby girl. The idea is to walk to Thailand. I am four. My dad walks ahead leading us the only way he knows: with an iron fist, cold eyes, and the machete ready on its sheath. We walk stealthily, belly crawling past dead bodies half-buried in the muck. We wade through rice paddies at night, and hide during the day. I don’t know why my baby sister doesn’t cry. I am hungry and scared. One night my dad spots a Khmer campsite just a few yards away from us. He turns around and presses his index finger against his lips. Shh, he whispers. I start to sob. My mother covers my mouth with her hand to stifle my cries. My father looks back over his shoulder again and threatens to quieten me with his machete. So I cry harder. The machete flies out of its sheath. Lands nice and square on my forehead. The scar has been there since. The end.”

There was another round of tequila shots and another G&T. You sighed hard. Your beautiful face looked like a tsunami warning. I was afraid that I wouldn’t know what to do with you if your tidal wave of memories reached land right there in the sports bar.

“Do you go back to Cambodia often?” I asked.

“What for? I don’t chase ghosts. Wait, I don’t believe in ghosts.” You laughed loudly, slapping your thigh and rocking your body back and forth, amused by your own hilarity. “I haven’t set foot in Cambodia in 30 years and that’s the way it will be until I die.”

“What’s the long version?” I asked.

You licked the salt off your hand, popped the lime wedge in your mouth and downed your third tequila shot.

“That one, you can Google,” you said.

You entered a limbo stage between sober and drunk. Buzzed, you let out a few glimpses into what the long version looked like. Something to do with your family catching a bus at some point during your escape from Cambodia, a decent-looking woman on board cooing into your baby sister’s weak face, and your mother understanding the gesture as a sign, handed the baby to the stranger. Giving the baby away was to give her a chance to survive. The long version included a scene at a rice field outside the refugee camp in Thailand in which your father did something to your older sisters that a good man wouldn’t do to his daughters. The long version had something to do with your brothers following your father’s example, completely inhabiting and re-enacting his legacy of abuse. Something to do with your six-year-old naked body crushed by the weight of your brother’s chest and how you stared at him, unafraid, full of love and convinced that whatever game he was playing with you it would stop by the sheer power of your gaze. And it did. How your mother, fully aware of the transgressions and therefore silently complicit in the violence inflicted on her three girls, had chosen to do nothing.

I felt like throwing things, putting fists through walls, punching patrons, and setting forests ablaze. I felt like screaming. Like if I opened my mouth the words would come out thick and incandescent, like lava.

In the background, Gretchen Wilson sang Redneck Woman. You started to tap your fingers on the table. “I’m just a product of my raising, I say, Hey y’all and Yee-haw,” you said in a singsong tone.

You mellowed down, the tsunami was gone; it had retreated into the ocean, taking away with it all the salt and the hurt. You had unburdened, your spirits lifted in a cloud of lightness and tequila, and your Cambodian past was someone else’s story. The bits and pieces you shared with me that night were the parts of your life you were trying to forget. The bits and pieces you shared with me that night were the foundation blocks upon which I have, over the years, re-created your past.

Five years after our conversation, I came to Cambodia thinking of you, the pain that was inflicted upon your family, and the hurt you were spared by escaping. In 1979 when Cambodia was liberated and Pol Pot’s regime fell, more than 300 killing fields were found throughout the country. Out of the 8 million Cambodians in 1975, fewer than 5 million had survived. The Khmer Rouge killed more than one out of every four Cambodians.

Yesterday in Batambang, on the quaint shores of the Sangkae River, there was a Zumba class. The instructor had secured the speakers to a rack on the back of his motorbike and the attendees, all women, danced to his instructions. They were gentle routines, in accordance with the modest Cambodian way; no hip gyrations, no chest pumping, no bottom-slapping motions, no hooting, and no cheering. It was more like a gentle line dance, a morning class taught at a seniors’ centre. Some of the women appeared to be in their 40s and 50s, old enough to have lived through the bloodbath of the ‘70s. I wondered how the woman to the right, the one with the flower-patterned blouse and straw hat, clumsily doing a cha-cha-cha, had made it alive. I imagined her laying at the bottom of a mass grave, crushed by the weight of her neighbours’ dead bodies, breathing quietly through her sister’s blood-soaked dress lying on top of her, praying for the Khmer Rouge comrades to leave them behind to rot under the sun, so she could crawl into the world and live to dance today.

*****

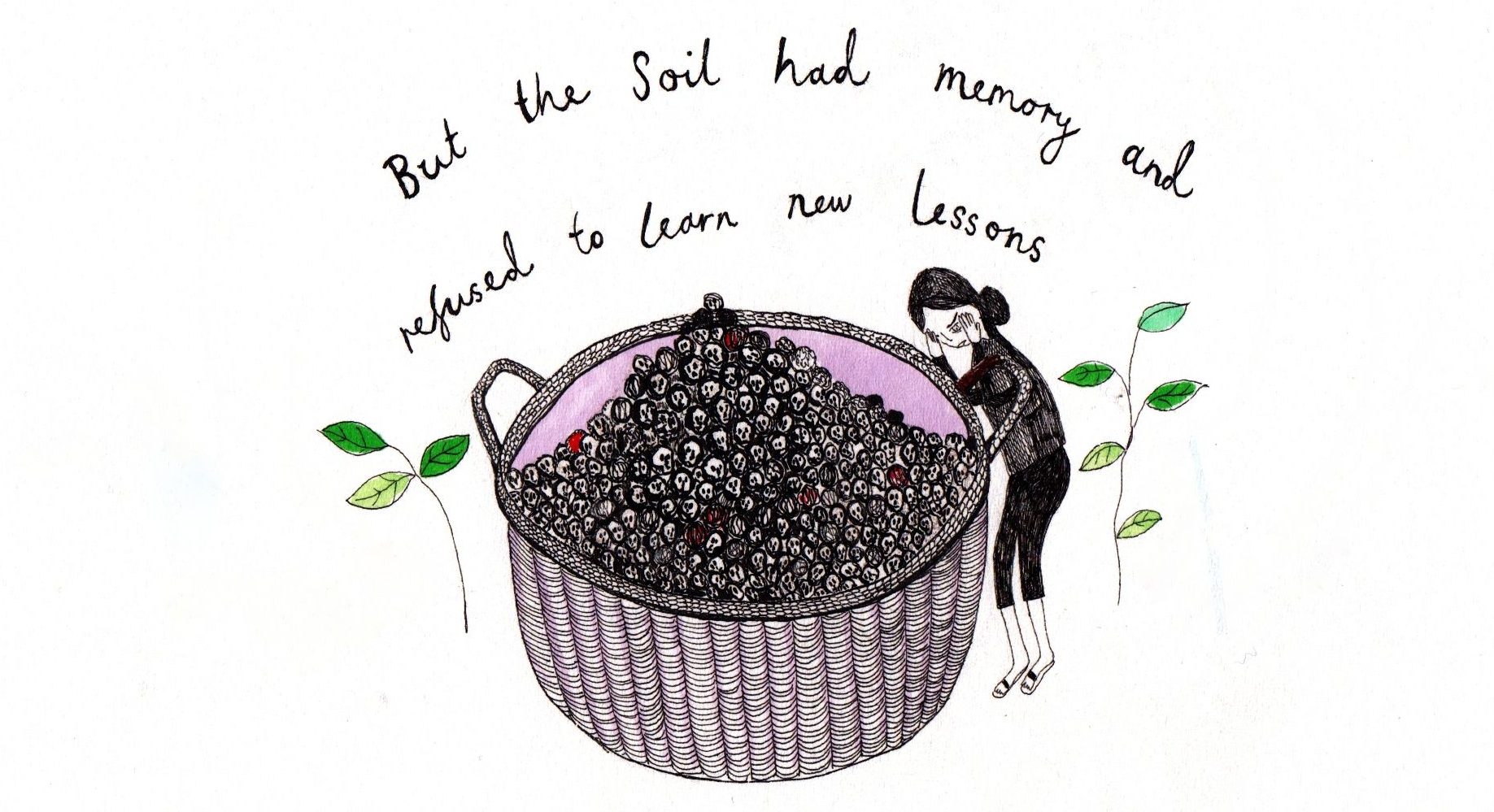

People say that pepper is Cambodia’s natural treasure; it produces the world’s best because of the quartz in the soil. However, this was nearly lost forever in the 1970s, when the Khmer Rouge ordered that Cambodia’s pepper vines be grubbed up and replaced with rice paddies. Pol Pot’s regime believed in the myth of Angkor — the capital of the Khmer empire — as a rice production machine, and because of this blind conviction, he and his henchmen put a whole nation through forced labour to achieve the production levels they assumed had been reached by their ancestors. Armed with nothing but this false historical fact they went through every means necessary to turn the entire population to the production of rice. But the soil had memory and refused to learn new lessons.

Under a punishing sun and 90% humidity, the owner of the pepper farm in Kampot — the country’s pepper capital — tells me the wonders of pepper. It can be harvested every year from February through May. Green peppercorns are removed from the stem, boiled for two minutes, and then left to dry in the sun for one week. Then they turn black. When black peppers get the skin removed — so they aren’t quite as spicy — they turn white. Green peppercorns that have been left on the vine for four months longer turn red. They retain their colour when dried and are the sweetest and most expensive variety because they take longer to mature. I begin to think of pepper as a chameleon vine, one that embodies the Cambodian spirit of survival, one that can either sweeten your tongue or sear your tonsils all the way to the source of life itself, depending on how you treat it. Then the owner tells me that in the ‘80s, after the Khmer Rouge surrendered their weapons, the new government gave most of the pepper fields in Kampot to former combatants in an effort to re-incorporate them into Cambodian society. The beautiful pepper-chameleon metaphor disappears. From then on I walk around afraid of looking at the farmers in the eye; anyone in their 50s and 60s is a possible murderer, anyone who was a child in the ‘70s either carries the scars of years of hunger and forced labour or has blood on his hands. What if I buy pepper from a torturer? From someone who is not entitled to touch this national treasure? What if, unbeknownst to me, I strike up a conversation with a pepper farmer who happens to have been the man in charge of beating children against the killing trees, like dusty Persian rugs?

In Phnom Penh, a tuk-tuk driver takes me along the Mekong River and its sad-looking esplanade. “Very nice,” he says, his face turned back in my direction, his hand pointing at the littered corniche. I see stray dogs, excrement, plastic bottles, rotten food covered by clouds of flies. “Yes,” I say.

He takes me to Chaktomuk, the confluence of the Tonle Sap, Mekong, and Bassac Rivers, along which some of Phnom Penh’s most important cultural sites as well as dozens of pubs, restaurants, and shops sit.

“This is nice,” I shout over the traffic noise. “Yes. My country very beautiful,” he shouts back. He drives past the Royal Palace, that complex of buildings flanking a silver pagoda filled with golden Buddha statues. “You want picture here?” he asks. “No, thank you. Keep going.”

Next door is the rust-red National Museum, where a statue of the Leper King is displayed among 5,000 artefacts. On a narrow two-lane street, he drives abreast three other tuk-tuks. At a traffic light, our vehicles are so close that I could hold hands with the passengers on both sides.

He takes me to Wat Phnom, a small hill crowned by an active pagoda that is considered the founding place of Phnom Penh. He turns right then left, gets into a roundabout, and points at the centre of the traffic circle at the intersection of Norodom Blvd and Sihanouk Blvd. There, amidst tuk-tuks, mopeds, pedestrians, and the unbearable traffic noise of the city, stands the Independence Monument, an exquisite memorial resembling a larger-than-life lotus-flower bud adorned with multi-headed cobras. He drives past the Central Market (Phsar Thmei), a landmark building of four wings that converge in a soaring dome at the hub. He makes a series of perilous turns, and before I know it we are on Ven Sreng Blvd heading south to my final destination.

I pay $6 to enter Choeung Ek and brace myself for this treasure hunt for body parts. The moment I put my headphones on to listen to the audio guide, something gets lodged in my windpipe. This place used to be a commune of Chinese immigrants, a prosperous orchard where whole families grew rice, corn, and watermelon trees. When the Khmer Rouge seized the country in 1975, under their ultra-communist regime, Choeung Ek became an ad hoc place for execution, and a dumping ground for the bodies of more than 17,000 Cambodians, most of whom had been previously tortured in the infamous S-21 Prison (now the Toul Sleng Genocide Museum). Choeung Ek is a killing field.

The land is filled with ground depressions framed by sandy footpaths. Each depression is a mass grave. I walk around in rectangular meanders, trying not to step on human bones shining white under the sun. I don’t know where to look. I’m surrounded by human suffering, death, decay, impunity. Stop number five reads: “MASS GRAVE OF MORE THAN 100 VICTIMS CHILDREN AND WOMEN WHOSE MAJORITY WERE NAKED”. A waist-high bamboo fence has been built around the grave to keep visitors from stepping on human remains, to give those underneath the respect and dignity they didn’t have when they died.

Stop number six reads: “MASS GRAVE OF 450 VICTIMS”. Westerners leave their bracelets on the bamboo sticks as a token of recognition, as a way to say that although they didn’t bear witness to the atrocities committed here, today they pay their respects to those senselessly arrested, interrogated, tortured, murdered, and buried right beneath their feet. Or maybe it’s collective remorse. Maybe they know about the half a million tonnes of bombs the USA dropped on Cambodia during the Vietnam War, which may have killed as many as 300,000 people, forced hundreds of thousands out of their villages and into Phnom Penh, and made many who resented the bombings or had lost family members join the Khmer Rouge’s army. Maybe they leave their bracelet as an admission of guilt and an apology.

A young tourist pulls a selfie stick out of her backpack and poses by stop number seven. “MASS GRAVE OF 166 VICTIMS WITHOUT HEADS”. She looks straight into the lens, her thumb at the ready on the shutter. I have violent thoughts. She takes two steps back so that the sign is more prominent in the shot. Her iPhone goes click. She removes her bracelet with the word Cambodia embroidered across it, leaves it on the bamboo fence, and takes another selfie. My thoughts grow darker. I need a break.

I tiptoe my way around mounds of sun-bleached bones sticking out of the ground like flags. The signs read “DO NOT STEP ON HUMAN REMAINS”. I follow a path that takes me away from the excavated graves. There is a lake and an embankment built to protect Choeung Ek from flooding during the rainy season. I sit on one of the benches to catch my breath, to get my head around this beyond-comprehension violence, to try to understand how a group of depraved lunatics managed to bring a whole country to its knees. There is a grove of fruit trees, a rice field, and birds flying over my head. A cool breeze caresses the lake, leaving stretch marks on its quiet waters. It’s almost a beautiful place.

Stop 17 on my macabre treasure hunt is the Chhrey tree, or Magic Tree. I think it’s magic because it looks like a Bodhi tree, the type under which Buddha attained enlightenment. But there is nothing magic about this tree. From its branches the Khmer Rouge hung loudspeakers blasting out revolutionary songs to cover up the screams of their prisoners being murdered, to give neighbours the impression of nightly political meetings. The Magic Tree, I repeat in my head. The Magic Tree. I begin to sob on and off, like a leaky tap. By the time I reach the last stop, I want to inhabit a different body, one which hasn’t heard the testimonies on the audio guide, one which has been spared this bloody past that’s frighteningly recent. I want to unhear, to unsee, to unwitness. The last stop is the Glass Box containing bone fragments, shreds of clothing, and teeth, which since the last grave excavation in the 1980s have come to the surface after heavy rains. Next to the box is a small structure resembling a bird house crowded with incense sticks and flowers: an ancient Cambodian tradition of honouring the deceased and offering a dwelling place for the spirits that have not found rest. All of it drowning under an anachronistic blanket of bracelets left behind by tourists.

The truth is, I’m here under the Killing Tree because of you. It is my convoluted way to honour the circumstances that brought you to me in a YMCA in central Florida. Of all the stops here at Choeung Ek, this is the one that hit me square in my throat. The realisation of what had happened on this tree trunk, made me want to switch species. Here in this pit were found the bodies of more than 100 women and children. Survivors say that Khmer Rouge soldiers would come at night, and in the glare of fluorescent lights they grabbed babies by their legs, smashed their heads against the tree trunk, then tossed them into the pit while their mothers watched helplessly. Then they killed the mothers. It was all justified under the Khmer Rouge slogan: To dig up the grass, one must remove even the roots.

The audio guide whispers in my ear such horror, such detailed account of torture and suffering, that it crosses my mind that maybe my audio is different from everybody else’s. It whispers that the people who discovered this place found blood, brain, and fragments of bone on the bark of the tree. This can’t be true. I refuse to believe that human beings can do this to their fellow humans. But it did happen. Here and in Nazi Germany, Rwanda, Chile, Russia under Stalin, Colombia, Argentina, China. Our history books are stained with cases of genocide, such a dirty word. The tree bark is now covered in the ubiquitous bracelets, a sort of all-creeds-and-nationalities shrine, a colourful trunk that looks like something you would have found in Woodstock, a hippie place of pilgrimage, not a burial site. Next to the tree, a signpost reads: “KILLING TREE AGAINST WHICH EXECUTIONERS BEAT CHILDREN”.

I’m not sure why your mom and dad did what they did. I don’t know what kind of crosses they carried on their shoulders, or what deep scars they hid under their clothes. I’m not sure what degree of ignorance leads to what degree of violence. I don’t know what compelled your brothers to follow in your dad’s footsteps, to dress in his shadow, and to harm rather than look after you and your sisters. I wouldn’t attempt an explanation to any of it. But I know this, despite what you told me on that night of G&Ts at the bar around the corner from the YMCA, you love your family very much. Your dad is long gone, but your sisters, brothers, and mom get together regularly. Collectively you live like any American family with a twist: you eat Cambodian food, sing to American country songs, go to the Buddhist temple in Tampa, celebrate Christmas and Chinese New Year. All of you are diehard Florida Gators fans, and your wardrobes share the green gator embossed on shorts, jackets, hats, even bibs. On Thanksgiving you and your family eat the biggest turkey in the whole of Florida and flank it with an array of Cambodian food. There is mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, and Khmer noodles. There is corn bread, coconut-based curries, and deep-fried fish called Trey Dang Dau. You all eat on the floor like a Cambodian family, and after the meal the TV is on and you watch football together. Cans of cold beer get passed around. Your brother sits cross-legged and props your daughter in the crook of his legs. She slurps a root beer float. There is love in his eyes and hers, and not a trace of suspicion in anyone’s. I’ve seen pictures of your mom. She looks ancient, but happy, always surrounded by family, always sandwiched between kisses and hugs. Everyone seems to have healed. To have moved on.

So, I won’t stir things up.

I’ll tuck my memories of this tree, where you could have died, in the back of my brain, right beneath my heart, between the folds of my woman soul. And I will never tell you what I saw.